Dr Arthur Randall Jackson is sometimes known as the “father of British arachnology”. Born in Southport in 1877, he studied Medicine and Zoology at Liverpool before setting up a practice in Hexham before moving to Chester in 1905. He was described by compatriots as of rugged build, both strong and tough, and he could be cynical, but also kind and sensitive. As a GP, he was noted for his accuracy in diagnosis. He described himself as a “….cyclist, spider hunter and bird watcher.” He was a distinguished amateur scientist and became an acknowledged expert on British spiders, discovering 47 new species. He wrote a number of papers and books on the subject and won the Charles Kingsley Medal for his work.

On the outbreak of the Great War, he enlisted in the Royal Army Medical Corps and was appointed a Captain and the Medical Officer of the 9th Seaforth Highlanders, with whom he served in France and Flanders from March 1916, until the end of the War. He was noted by his men for his jokes and stories, as well as what some of them considered his eccentric habit of collecting natural history samples on the front line. In late 1917 he was awarded the Military Cross for “… conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty….in his efforts to get in casualties, repeatedly going forward through enemy barrages…” (Edinburgh Gazette, March 11th 1918)

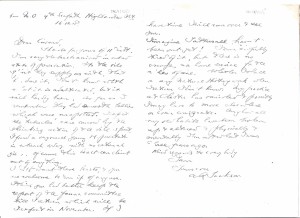

His links to the Manchester Museum came through his membership of the Cheshire and Lancashire Natural History Society and a longstanding friendship with the Museum Director Walter Tattersall. He seems to have donated samples to the Museum long before the War and is fleetingly mentioned in the 1915 Museum Year Book. He sent the samples he collected in the trenches back to Manchester Museum and maintained a lively correspondence with the Museum`s temporary wartime director, Thomas Coward. It’s through some of these letters that we see his zeal to collect and study, even in the midst of war, and his personal feelings through letter such this sent to Tattersall, Director of Manchester Museum, then serving in the Royal Garrison Artillery, dated September 1918:

“Imagine Tattersall hasn`t been over yet! I am awfully tired of it, but there is no escape, nor home service for the likes of me. Whether I shall have any Natural History work when I return I don`t know. My practice at Chester has vanished and possibly I may have to move elsewhere or even emigrate. Anyhow all my old habits have been broken up and retired and physically and mentally I`m not what I was three years ago.” (Manchester Museum Collection)

After the War he didn’t emigrate, but re-built his practice and became a keen gardener and a collector of art and antiques. On his death in 1944, he donated his personal collection to the Atkinson Museum, Southport in memory of his son who was killed with the RAF in World War Two. The items he sent back to Manchester Museum from the trenches now form part of the Natural History Collection alongside some of his wartime letters.